Do you have any idea what's going on within your teeth? I'd never given it much thought until April, when one of my molars revolted, and my teeth became the only thing I could think about. As everyone who's ever had a toothache knows, the quaint discomfort that the name conveys doesn't represent the immense anguish that a toothache can generate; at times, the pain was so intense that I couldn't use my laptop.

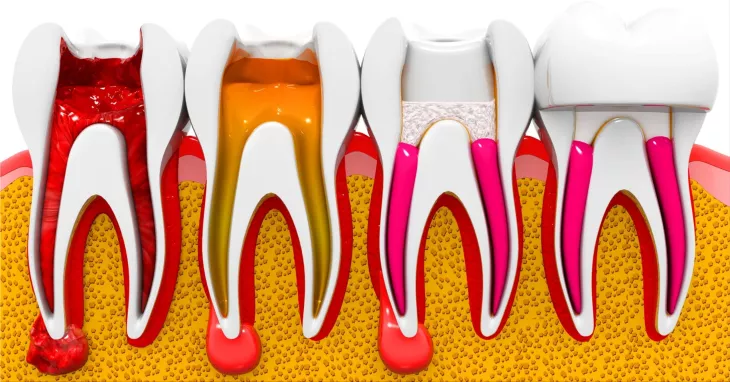

After a week of inconclusive X-rays, a failed round of antibiotics, and fistfuls of an internet-recommended ibuprofen-acetaminophen combo, I was eventually referred to an endodontist—a specialist who treats oral pain—to meet my tormentor. I'd shattered a tooth, which the endodontist was ultimately able to find using a CT scan. I was pumped up with novocaine moments later, and after a few minutes of drilling, the endodontist asked whether I wanted to examine the source of all my pain. "Yeah," I breathed largely through my nose. He held up his forceps, and dangling from the tip was what appeared to be a miniature, leafless tree depicted in the bright crimson of fresh blood. It seemed too flawless, its edges too distinct, like something made for a film rather than an average lump of human viscera.

Nothing was going the way I expected. One of the most often dreaded treatments in contemporary medicine is recommended when a tooth splits: a root canal, which is so infamously painful that its name has long been a popular metaphor for a long journey through suffering itself. That's why I was in the chair that day: to have my tooth drilled out and its nerves and vasculature extracted. After the CT scan, I'd asked the expert to root-canal me right then and there while I was experiencing the boldness of sheer desperation rather than making me come back the next day. That's when things started to become strange. When the endodontist said we were done, I assumed he was joking—pop culture had spent years preparing me for an event that no longer existed. After the local anesthetic had worn off, I ate supper as if nothing had occurred.

My tale is not an unusual one from the last year and a half. I joined many other Americans in what appears to be a pandemic tooth-cracking feast due to a mix of acute stress, new medicine, and what had previously been a modest inclination to grinding my teeth in my sleep. According to a February poll conducted by the American Dental Association, over two-thirds of dentists reported finding more broken teeth in their offices during the pandemic than previously, and 71% reported more excellent rates of bruxism, which is involuntary grinding that can lead to cracks. Yet, according to my endodontist, the root-canal industry was thriving.

Asgeir Sigurdsson, chair of the NYU Department of Endodontics, confirmed that this is still the case six months later. Not only are individuals anxious, but many people who would have had problems detected at a routine appointment in 2020 avoided their exams due to budgetary constraints. Then, as Americans became vaccinated, dentists' appointment books began to fill up rapidly, which may have discouraged some patients from scheduling a cleaning.

Checkups are easy to put off—even the most primary dental treatment is expensive and, at best, physically painful, and around one-third of American people lack coverage for any portion of it. In addition, submitting to a cleaning increases your chances of being informed that you require an expensive, unpleasant operation, and some unscrupulous practitioners take advantage of patients' incompetence to evaluate their dental health.

People who require a root canal are usually aware that they need one. Cracks, diseases, and severe degradation are all readily apparent. According to Sigurdsson, each tooth has 1,500 to 2,000 nerve fibers at its core, with the majority of them being a sort of receptor that solely detects pain. (If you've never contemplated the complete absence of dental pleasure in your life, well, there you have it.) It's maybe not surprising, therefore, that getting all of those nerve fibers scooped out of your tooth used to hurt—enough to produce an understanding of the root canal that has lasted long beyond its accuracy. Thank God for medical and technological advancements.

Except that there haven't been many notable advancements in root canal therapy. Sigurdsson has been conducting the technique regularly for 30 years, and it's essentially unchanged from when he learned it in dentistry school.

Even if everything is done right, none of this guarantees that every patient's operation is now painless. The novocaine injections themselves are rather unpleasant, and for patients who are afraid of needles may be scary. According to Sigurdsson, some individuals with complex problems, such as significant nerve inflammation, will not respond adequately to the current anesthetics. Furthermore, some data shows that anxious persons about their surgery are more difficult to anesthetize, possibly because their fight-or-flight response or another neurochemical reaction hinders the anesthetic's efficacy. However, Sigurdsson assured me that the vast majority of his patients were pleasantly pleased.

If generations of dental students have been instructed to numb their root-canal patients before plunging into their pulp thoroughly, why has the procedure's reputation endured? It might be because root canals are thankfully uncommon for most individuals. Many patients who may require more than one surgery in their lives spend decades between them, unknowing that the next one will be less painful. If you've never had a root canal, you might recall your parents moaning about a particularly nasty one.